Foto: © Fotonatura.org

The seabream is the most common fish in the world belonging to the Sparidae family, and one of the most common species in the island of Fuerteventura. It’s an exceptional inhabitant in our neighbour islet of Lobos, and we can watch it everyday in our snorkelling sessions.

Its Greek name is “Diplodus”, steming from “diplos” and “odus” (double tooth), and it makes reference to the fact that it has two different kinds of teeth: incisors, flat and sharp at the front part of the jaws, to cut and bite off (some species even present sharp canines); and molars, at the back, to crush the food.

The seabreams’ habits change with age, so when they are young they are omnivorous and as they grow up they become carnivorous, feeding on molluscs, some of them with shell, and on invertebrates they dig up. Within the different species, some of them are gregarious and you can find them in schools, looking for protection from potential predators or just around a food source, as for examples mussels. Other species, like the sharpsnout seabream or the zebra seabream, go alone and you can hardly see them in groups of more than 3 adult specimens.

Another characteristic of this family is that they are hermaphroditic, and the first stage of their lives they are male, and they become female later on, which is why the size of the female specimens is considerably bigger than that of male ones.

It’s a combative species, and during the mating season they can be quite aggressive, even endangering the life of their own breeds. Their breeding season is Summer.

Here, in The Canary Islands, and specially in Fuerteventura, we have the five species that make up this family: white seabream, (Diplodus sargus), annular seabream (Diplodus Annularis), common two-banded seabream (Diplodus Vulgaris), sharpsnout seabream (Diplodus Puntazzo) and zebra seabream (Diplodus Cervinus).

All seabream species have reached the 50% of their maximum size at the age of 4.

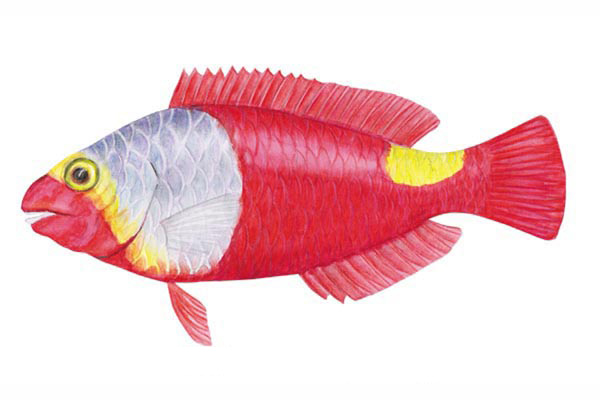

The white seabream (Diplodus sargus)

This is the one we find more easily in Fuerteventura Coast, on rocky seabed as well as between seaweed and sandy seabed, in shallow areas, between 0 and 50 mts deep.

It’s grey, light or dark depending on the camouflage it needs, and it has flashing silver sides. Young specimens feature dark vertical and longitudinal stripes at its sides, and in some sub-species, like the Diplodus sargus sargus or the white seabream, they disappear completely when they become adults, except the one they have at their tail. In other sub-species, like the Diplodus sargus cadenati, or black seabream, the stripes are lengthwise, and they never disappear. In the case of the Diplodus sargus lineatus the vertical stripes don’t disappear either.

They have 12 bones in the dorsal fin, and 3 in the anal one, and a black border in the tail fin.

They can be, maximum, 45cm long, weigh a maximum of 2kg, and live around 10 years.

Annular seabream (Diplodus Annularis)

Silver uniform body with five vertical dark lines which disappear in the adult years. The pelvic fin and the beginning of the anal fin are yellowish. It’s very common in meadows of marine phanerogams, among 0 and 15m deep. The biggest specimen that has been found is 22cm long, and it lives around 7 years.

Common two-banded seabream (Diplodus vulgaris)

This species doesn’t have any vertical stripes in its body, just one behind its head and one near the tail, and what characterises it are the thin longitudinal yellow stripes, a slightly blue colour in its head and a reddish stain on its eyes.

It’s often found in rocky areas, no deeper than 50m. The biggest specimen was 36,5m long, with a weight of 1,3kg, and they usually live around 9 years.

Sharpsnout seabream (Diplodus puntazzo)

It also has vertical stripes that disappear when it becomes adult. It’s called this way after its snout looking like a beak, with tilted incisor teeth.

It inhabits deep areas, between 10 and 150m deep. It’s usually a bigger specimen, around 60m long, weighing up to 1680kg. It usually lives around 9 years.

Zebra seabream (Diplodus cervinus)

Also known as real seabream because of its big size. Its body is slightly convex and it features vertical dark brown and silvery lines, which do not disappear with age. Old specimens have quite thick lips. It inhabits very deep areas, between 30 and 300m deep.

The biggest specimen is 55cm long and it weighs 2,74kg, although in spear fishing they have found 5kg specimens. It is the most long-lived of all the seabreams, being able to live up to 17 years.

The seabream is a very coveted fish in sport fishing, as it’s very easy to catch, mainly the zebra seabream. In Spain, the smallest size allowed to be caught is 22cm.

It’s a very popular fish in the gastronomy of Fuerteventura, due to its versatility (it can be grilled, steamed, baked or fried) and also because it has a soft flavour and meat, rich in vitamins and minerals.

Fuertecharter’s team